In the last blog piece we became masters of body axes, and in this one we are going to become more familiar with describing how different parts of the body are organised in relation to one another. Why do we need to standardise this? Well I’ll tell you!

Let’s take an everyday situation that you, as a medical student, may encounter:

You’re at predrinks with your friends before a big medic night out, wearing an outfit fused together from the lingerie section at Primark and items frantically ordered from Amazon using the express delivery in your free student trial. Before you is a table full of assorted soft drinks, playing cards and alcohol; but you need your alcohol. You call out to your friend on the opposite side of the table, stood next to your particular bottle of Sainsbury’s Basics vodka, and ask him to pass you your drink. ‘Where is it?’ he slurs at you. ‘On the table’ you respond, to which he starts jerking his head, frantically scouring the table. He hasn’t a clue. ‘It’s next to the UV paint and the empty jug from Ring of Fire, right next to you’ you sigh. With a grin that only Smirnoff and the Coca-cola company can engineer, he hands you your drink. The rest of the night proceeds, as usual, into a forgettable stupor that ends with a DJ at the Ritz and some regrettable decisions better left for your hangover to deal with.

The abstract point I’m hammering home, through my pale attempt at humour, is that it’s not enough in anatomy to describe the general location of something. The more specific that we can be, the more helpful it is to clinicians that encounter the situation later down the line. Otherwise mistakes can be made. ‘A cut on the arm’ might narrow things down from saying that a patient ‘has a cut’, but it could be more specific by saying, for example, ‘This patient has a cut on the distal anterior portion of their left arm on the ulnar side.’

Fear not. These words will make sense soon.

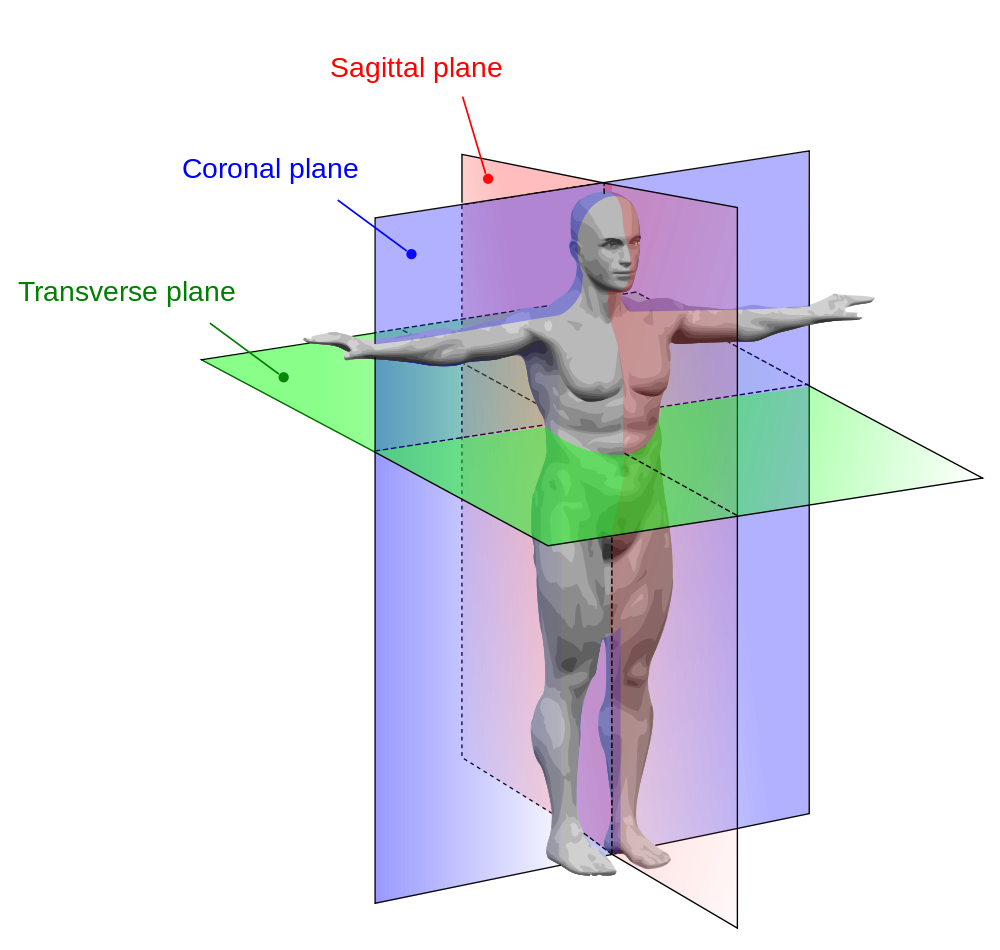

Anatomy is definitely a language of its own, but it follows a system. Orientating and relating things to each other in the body describes the location of something using a new set of unrelated four axes (Remember that we always consider the body in the anatomical position- stood erect, palms facing forward!):

1. Anterior-Posterior – This is the ‘front-to-back’ axes. If an object is in front of something then it is ‘anterior’ to it. If it’s behind something then it is ‘posterior’ to it.

2. Superior-Inferior – ‘Top to bottom’ axis. If something is ‘superior’ to an object then it is above it in the body. If it is ‘inferior’ then it is below it.

3. Medial-Lateral – This axis is essentially a way of saying whether something is close to the midline of the body, or further away. The inner side of your thigh, for example, would be the medial side of it- close to the midline of your body’ and the side facing the outside would be the lateral side.

4. Proximal-Distal – The ‘Near-Far’ axis (or the ‘Celine Dion Axis’, if you will) tells us whether we are looking at something close to the trunk of the body, or further away. For example, the part of your calf closest to your ankle would be the distal part of your calf, but the part just below your knee would be the proximal part, because it is closest to the trunk.

http://image.slidesharecdn.com/planesaxes-121223101724-phpapp01/95/planes-axes-7-638.jpg?cb=1403962866

There are some variations on the axes mentioned above, depending on the body area. Things in the arm can be simplified into ‘radial’ and ‘ulnar’ sides, as opposed to ‘medial’ or ‘lateral’. Similarly, in the leg things can be classified ‘tibial’ or ‘fibular’. You will also encounter the terms ‘dorsal’ and ‘ventral’ when studying anatomy of the brain, where ‘dorsal’ refers to things that are ‘on top’ and ‘ventral’ refers to something ‘on the bottom’. Other variations do still exist, but you’ll encounter them in time!

There are no strict rules on what order that you orientate a structure, nor are there standard rules on any minimum or maximum amount of specificity. Some clinical situations may require you to measure something with a ruler, exactly, and others will suffice if you can say which body part something is on. The further along the course you get, the more you’ll become familiar with using anatomical terms- trial and error in your anatomy sessions is crucial to learning!